|

By Jerry Tardif

Let me start by saying that I'm not purporting to be an expert on bits.

But I've been troubled to find that many people know far less, yet are more than happy to continue to pass along what they've been told as gospel, right or wrong.

The problem is that lots of people were told wrong, heard wrong, understood wrong, or got some other part wrong.

The sad result is that a lot of legend, misinformation, and misunderstanding is passed along from person to person and generation to generation about bits and bitting.

That's really too bad because it means that we're often using the wrong bit for the wrong reason and getting less than stellar results at controlling our horses.

Worse, we can be causing our horses severe pain and/or partial asphyxiation without realizing it.

Snaffle Bit with Copper Mouthpiece

Having an engineering background, some of the things I was hearing about how bits worked just didn't make any sense.

So I set about studying and learning more about them.

It initially seemed overwhelming because there are so many different bits out there.

But I soon discovered it wasn't as complicated as I initially thought.

Here's some of what I learned:

The topic of bits is complex because several components are put together in many different ways.

More importantly, there are no real standards.

Each manufacturer can create a new variation, combine parts as he wishes, and then call it anything he wants.

For example, most people think of snaffles as a mild bit — but they can be quite harsh.

The only aspect that I've consistently seen with snaffles is that every one was a direct-pressure bit; that is, I haven't seen one that used any form of leverage (at least not yet).

So let's try a different approach to understanding bits.

Let's look at the parts of a bit.

This way, you'll be able to look at a bit's construction in a catalog or tack shop and understand its mode of operation, its harshness, and whether or not it is direct-pressure or leveraged, and if so, about how much.

You won't care what the manufacturer or anyone else calls it because you'll already know that a bit's name is not always indicative of its operation.

Let's start by identifying a bit's components.

- The Mouthpiece

The mouthpiece is the part of the bit in the horse's mouth.

It can be mild or extremely severe.

Severity can be caused by the bit being twisted, or serrated.

The mouthpiece can be solid or split in the middle (jointed).

It can be split once or twice, called single- or double-jointed (it can even be split more, but that's less common).

The center can be a plate or a roller.

Rollers can be made of different metals to increase salivation.

There can also be key or tongue bits.

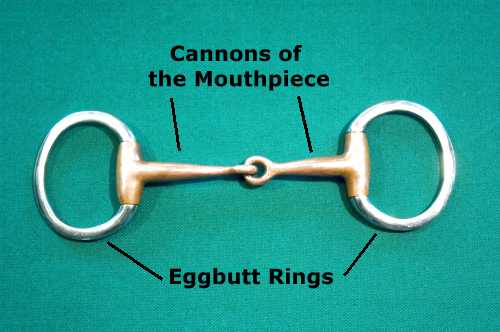

- The Rings or Cheek Pieces

These are the end pieces that often, but not always, form an enclosed loop.

There are D-rings, Egg-butts, loose rings, Baucher (also known as a hanging cheek), full-cheek, half-cheek, Fulmer, full-spoon, flat-rings, and likely more.

- Optional Parts

There are some additional parts that are not used on all bits:

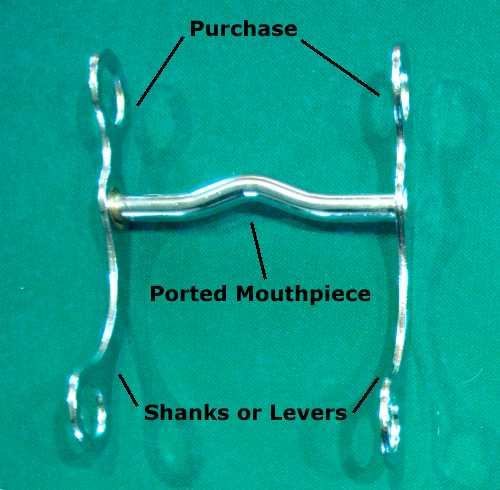

- Port

This is an upper loop in the center portion of the bit.

The port can be a mild loop or a bigger, harsher loop.

It can place pressure on the tongue, but it can also give relief by giving the tongue more room.

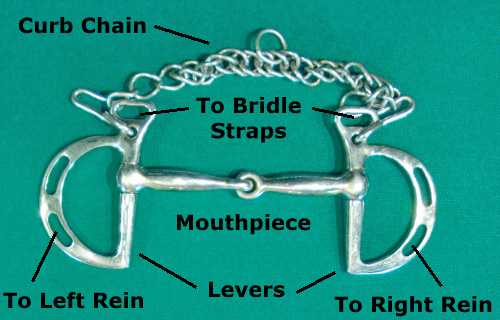

- Curb Chain

This is a chain that runs under the horse's mouth.

It's purpose is to squeeze the mouth between the bit and the chain — not very nice for the horse.

- Shanks

These are metal strips or rods.

The upper end connects to or makes up the cheek pieces and the reins connect at the bottom providing leverage.

That means the force you apply with the reins is multiplied, or "leveraged".

The longer the shanks, the greater the multiplier and the greater the force you're applying to your horse's mouth.

There may be other parts appearing on some bits, but these are the ones most common.

As you can see, a bit can be made in many different ways.

It is because of this reason that bits appear to be so numerous and confusing, not only to the beginner, but to anyone that hasn't studied different bits and their parts.

Now, let's take a look at each part in turn to see its variants and what they do.

Mouthpieces are the "working" part of the bit.

Bits, along with other aids, provide a way of indicating to our horse which way to go and when to slow down or stop.

In some disciplines, the function goes further than simple control.

For example, smooth Snaffles or smooth rubber bar bits are sometimes used for racehorses so that the horse can brace himself against the bit as an aid to running.

Or in dressage, the horse has to be "on the bit" for subtle and quick control.

Mouthpiece With Single Joint

|

Ported Mouthpiece

|

Bit Surface

A bit is thought of being gentle if the "cannons" of the mouthpiece are smooth and adequately wide.

The cannons are the parts of the bit in contact with the horse's bars.

But if they're thin, the cannons concentrate the force you apply when pulling back on the reins rather than distributing it.

Also look at the cannons surface.

Single and double twisted wire, slow twist, and saw chain bits are all very harsh because they use thinness and/or sharpness to cause pressure points.

Even with the softest hands of an experienced rider, these bits can be severe because a surprise pull can still occur if a horse turns quickly or if the horse trips while the rider has the reins back for a moment.

Bit Joint

Some bits have joints in the center, such as the Snaffle, Kimberwicke, Tom Thumb, and others.

When you pull back on the reins, the joint closes in what is called a "nutcracker" effect.

The mouthpiece puts pressure on the bars, lips, and tongue while that closed joint also puts pressure on the roof of the mouth if the rider pulls too hard on the reins.

As you begin to understand how bits work, it becomes obvious that they're all designed to use some degree of pressure or pain on the horse's mouth to maintain control — the Snaffle doesn't seem quite as mild as its operation becomes better understood.

With a smooth surface mouthpiece, it is more gentle than many other bits, though not necessarily gentle.

About this time, you may be starting to feel you're torturing your horse, and that is a possibility.

But a better way to view this is that it's very important for ALL of us riders to learn to properly handle and manage the reins so that we don't harm our horses.

It's possible to use the reins and bit as a signaling mechanism on cooperative horses rather than a way to force control.

Double-Jointed Bits

Double-jointed bits provide more room for the horse's tongue and less of the nutcracker effect making them somewhat less harsh.

But someone had the idea of twisting the cannons on some double-jointed bits, which again now makes those particular bits harsh.

Also look at the small piece in the middle between the two joints.

If it's flat and smooth, it's easier on the tongue; if it has a ball, it's harder on the tongue.

If it is an upward loop linked to the cannons, it can actually cut into the tongue and is very harsh; such as the Broken Segunda bit, which is a form of a D-Ring Snaffle.

Again, I point out that a bit is not gentle just because it's called a Snaffle or a form of Snaffle.

Roller Bits

Sometimes, you'll see a roller in the center of a double-jointed bit.

A roller is said to relax a horse by encouraging him to play with it using his tongue.

If the roller is made of copper, it will also encourage increased salivation.

A roller, in and of itself, does not affect the harshness of a bit.

Ports

A port is an upward loop in a straight non-jointed bit, such as a Pelham.

It's purpose is to increase control by pushing on the tongue as you pull harder on the reins. Ports come in various heights from low to quite high.

A high port may hit the roof of the mouth; if so, it doesn't touch the tongue and instead forces the cannons down harder onto the bars of the mouth.

As you can see, variations work by causing pressure (or pain) to some part of the horse's mouth.

Most of us are ok with a reasonable amount of pressure used as a signal mechanism.

Even using leg to turn or sidepass is no more than applying pressure.

But when one or more of these bit variations are used, or too much pressure is applied even with a mild bit, we're moving from pressure to pain as the control mechanism.

That's why it's so important to know how to properly rein a horse and proper technique should be taught to all students at the outset of their training.

Pelham Bit

By this time, you should be seeing that the name of a bit gives little indication as to its harshness and that we really do need to look at a bit's various parts to really know how it will operate on our horse's mouth.

Pick the wrong bit and you can unknowingly be hurting your horse.

Rings or cheek pieces are connected to the ends of the bit (the cannons).

The term "cheek piece" is used in several different ways, but most accurately defines the ends of the bit to which the bridle straps and reins attach.

So in reality, even the rings are cheek pieces.

However, if a bit has rings, they'll be called that or the name of the style of the rings (D-ring, Egg-butt, Loose Ring, etc.)

The term "cheek pieces" will usually be used when the bit ends have short or long rods or shanks and no rings.

An additional purpose of rings and cheek pieces is to keep the bit from being pulled through the horse's mouth.

The larger they are, the less chance it will happen, though it can put a lot of force on a corner of the mouth when you pull just one rein.

If your bit has full-cheeks, they distribute the force better, but can be uncomfortable on the sides of the horse's face.

If you use a bridle with a noseband, the chance of a bit sliding through the mouth is significantly lessened and is likely far less uncomfortable for the horse.

A loose ring is just a metal loop to which you connect the bridle straps and the reins.

Because it's loose, it can sometimes pinch the sides of the horse's mouth.

D-Rings and Egg-Butts don't slide or pinch in that way.

Curb Bits

Curb bits are a family and refer to leveraged bits.

Those are bits with shanks and chains.

The leverage comes from the shanks, but they almost always operate with a curb chain.

It's a two step process in that the chain should be loose enough to fit two fingers when the reins are released.

As you pull back, the horse should be responding to your signal. Only once you have pulled back enough to "use up" the slack in the chain will it start to have additional effect.

But remember, at that point, you've got the horse's mouth in a bit/chain vice and must be careful not to exert too much pressure.

Kimberwick Bit with Curb Chain

Range of Curb Bits

There is a wide range of curb bits.

The mildest is the Kimberwicke; at the other extreme are the high-leverage Pelham bits with 8 inch shanks, sometimes made even more harsh with the addition of a high port.

Such a bit is very powerful and must be used carefully and with very soft hands — your horse's mouth is at stake.

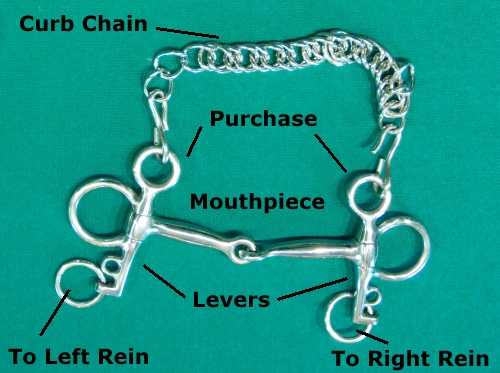

Recognizing Leverage in a Bit

Leveraged bits use levers, and their appearance can tell you that.

On a bit like a Pelham, the levers are straight peices of metal and are often called "shanks".

Bits with rings can look similar, but the effect on the horse can be quite different.

For example, I've heard riders mention that a Kimberwicke is a Snaffle with a curb chain — NOT TRUE!

A true Snaffle is an unleveraged bit — the force you apply is the force felt by the horse.

A leveraged bit multiplies that force.

Some kimberwickes are jointed bits and have rings with slots specifically for the bridle straps and other slots for the reins.

Another Kimberwicke design I've seen has a straight bar like a Pelham, may have a port, and can have smaller rings with no slots, but it still has the slots specifically for the bridle straps — they're the key.

The slots assure the reins will pull from a certain point and don't slip up or down the ring as they do on a snaffle.

Those slots furthest from the mouthpice provide the greatest amount of leverage — the force you apply to the reins is magnified.

When you add the curb chain, you've got a bit that is more harsh than a smooth snaffle, but not as bad as a longer shanked bit.

The point I'm trying to make is that it's very important to be able to recognize if a bit is leveraged or not.

Tom Thumb Bit

Tom Thumb bits are thought by some to be a mild bit.

But it's levers are usually longer than a Kimberwick, though shorter than a Pelham.

Add the "nutcracker" action of a snaffle or Kimberwick and it can be quite harsh if used incorrectly.

Shanks

Shanks, also called "levers", are the long sidepieces that hang down below a bit and attach to the reins.

The longer the shank, the more leverage the rider has and the more force he can apply to the horse's mouth.

The way to determine the amount of leverage you have is to compare the shank length above the cannons (the purchase) and the length below (the lever arms).

Divide the purchase length into the lever arm length and you have the force multiplier.

So, if the purchase length is an inch and the lever arm is seven inches long, the force you apply is multiplied seven times.

Such bits are meant to be used with small forces on the reins, usually in ounces of force.

If a beginner gets frightened and pulls with ten pounds, he/she is applying 70 lbs. to the horse's mouth — imagine twenty or more pounds of pull and consider what the horse is feeling on his mouth.

If a leveraged bit, such as a Pelham, is used without a curb chain, its effect is greatly reduced because the absence of the chain means that it can't be used to squeeze the jaw.

But if it has a port, the rider must remember that when pulled, that port will squeeze down on the tongue and the pull forces are magnified by the ratio between the purchases and the levers.

Bits with high leverage should be used only by experienced riders because untrained riders can pull too hard or roughly "ride the bit" hurting or injuring the horse's mouth, possibly severely.

Besides being an avid trail rider, Jerry Tardif is a technology consultant and a horse and nature photographer in SE Connecticut — see his work at: www.jerrytardif.com.

He is also co-founder and President of QueryHorse.

Back to Article Index

|